Why are courts unable to implement their own orders to protect our rivers?: The case of Sabarmati river pollution

By Krishnakant Chauhan

Today the intersection of environmental conservation and judicial intervention has emerged as a critical area of legal discourse in India, particularly in the context of river conservation.

In India rivers are integral to the cultural, economic, and ecological fabric of the country, and yet, many of them are facing unprecedented levels of degradation due to urbanization, industrialization, pollution, and encroachment. In this regard, the role of the judiciary in shaping environmental policy and governance cannot be overstated. Judicial activism has often played a crucial role in holding the government accountable for its responsibilities toward the environment, compelling them to take action where legislative and executive mechanisms have fallen short. The Judiciary has applied judicial principles like the Doctrine of Public Trust and the Polluter Pays Principle. While the judiciary has been assertive in many environmental cases, it has seemed to have lower its guards when the environmental issue would lead to raising questions on the faulty and lopsided ‘development’ model and reckless urbanization.

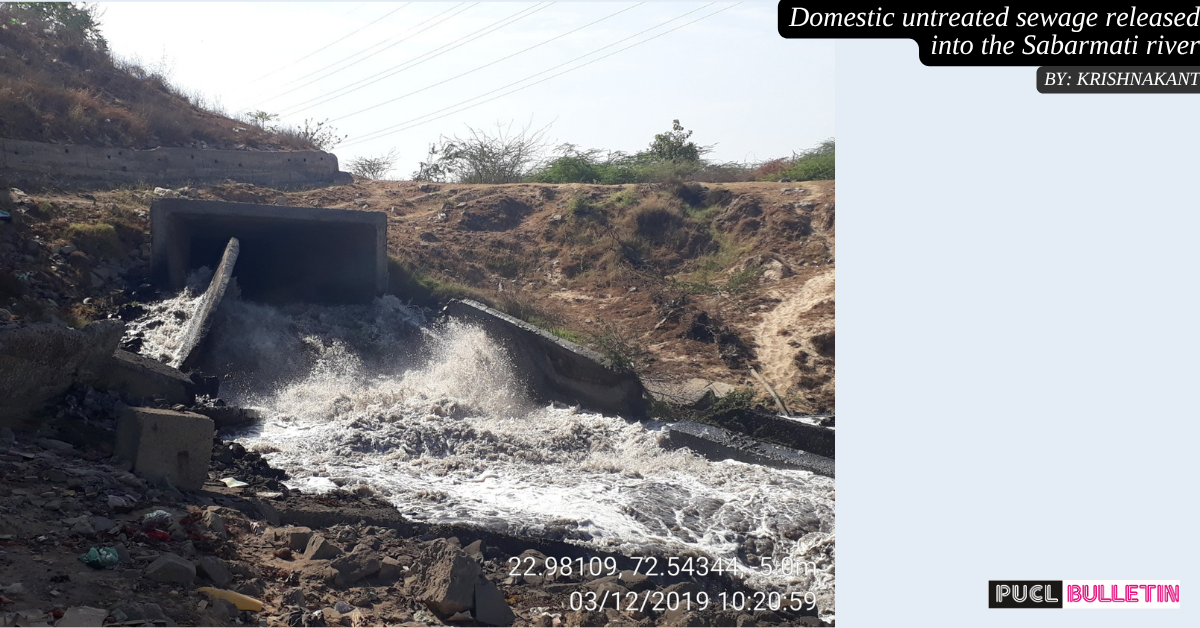

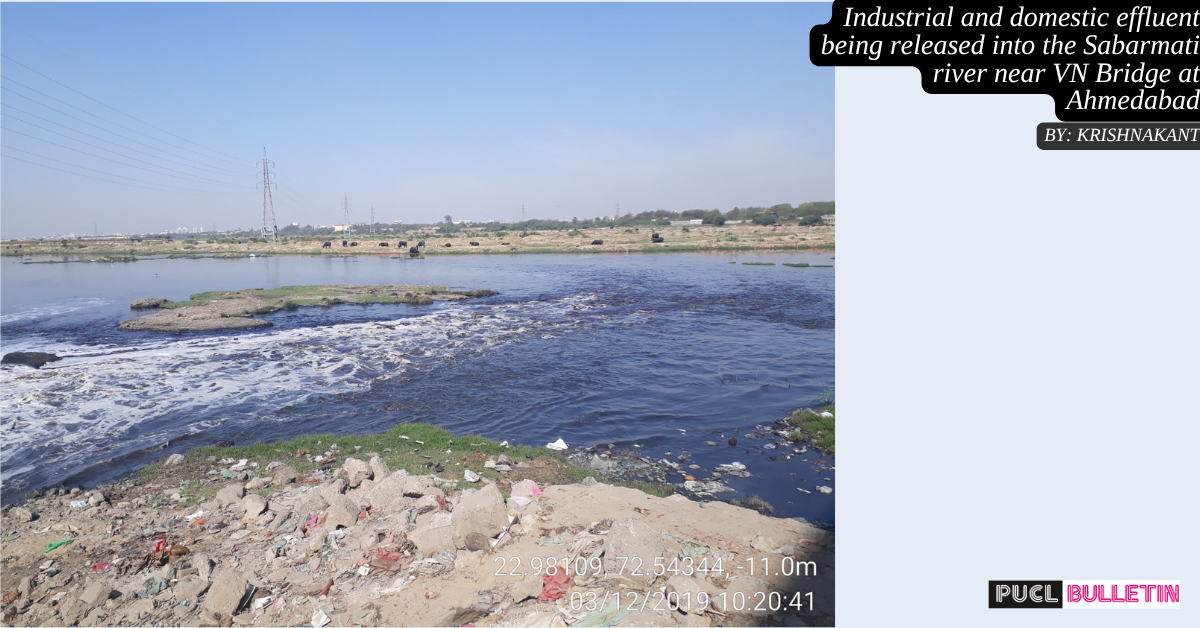

The recent drive to clean up the Sabarmati River front’s pond by emptying it, exposed illegal discharge of untreated sewage into the Sabarmati. This state of affairs is continuing after more than 8 years of the Supreme Court Judgement in Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti vs Union of India WP(C) 375/2012 and the ongoing WPPIL 98/2021 which was taken up suo moto by the Ahmedabad bench of the Hon’ble Gujarat High Court, then headed by Justice J.B. Pardiwala and Justice Vaibhavi D. Nanavati.

As the matter continues, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) has been submitting its progress reports before the bench of Chief Justice Sunita Agrawal and Justice Vaibhavi D. Nanavati claiming that ‘All is Well’ and there are no illegal discharge connections into the Sabarmati. The issue pertains only to the upgradation of Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) which when completely upgraded will treat the sewage as per the norms.

WP(C) 375/2012 – a landmark case to address river pollution:

In Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti (above), the Hon’ble Supreme Court bench headed by then CJI Justice Jagdish Singh Khehar, was very categorical when it said, “10. Given the responsibility vested in Municipalities under Article 243W of the Constitution, as also, in item 6 of the 12th Schedule, wherein the aforesaid obligation, pointedly extends to “public health, sanitation conservancy and solid waste management”, we are of the view, that the onus to operate the existing ‘common effluent treatment plants,(read – Sewage Treatment Plants) rests on municipalities (and/or local bodies). Given the aforesaid responsibility, the concerned municipalities (and/or local bodies), cannot be permitted to shy away, from discharging this onerous duty.”

The Hon’ble bench further stated, “The norms for generating funds, for setting up and/or operating the ‘common effluent treatment plant’ (read – Sewage Treatment Plants) shall be finalized, on or before 31.03.2017, so as to be implemented with effect from the next financial year……. In case, such norms are not in place, before the commencement of the next financial year, the concerned State Governments (or the Union Territories), shall cater to the financial requirements, of running the “common effluent treatment plants”, which are presently dis-functional, from their own financial resources.”

The judgement also laid down a timeline for implementing the directions and the National Green Tribunal was entrusted to supervise complaints of non-implementation of the instant directions and monitoring of the implementation deadlines. The bench felt that mere directions are inconsequential, unless a rigid implementation mechanism is laid down.

The judgement also allows ‘private individuals, and organizations, to approach the concerned Bench of the jurisdictional National Green Tribunal, for appropriate orders, by pointing out deficiencies, in implementation of the above directions.’

The bench fixed the responsibility of implementation on the states by directing that, “The Secretary of the Department of Environment, of the concerned State Government (and the concerned Union Territory), shall be answerable in case of default. The concerned Secretaries to the Government shall be responsible of monitoring the progress and issuing necessary directions to the concerned Pollution Control Board, as may be required, for the implementation of the above directions.”

The Gujarat High Court and its case concerning Sabarmati river:

The suo moto PIL initiated by the Hon’ble Gujarat High Court has been instrumental in correcting many lacunas leading to the release of pollutants into the Sabarmati River in the form of treated/untreated sewage and industrial effluents. The court formed a joint task force comprising concerned departments and experts to identify and address the factors and impediments leading to pollution being released into the river.

One of the central issues in this case is the inefficiency of the existing STPs. Reports indicate that many of these plants are not functioning optimally and fail to meet the standards set by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). The analysis of industrial waste water has revealed high levels of contaminants, particularly in terms of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) and color, which exceed permissible limits. This situation poses a significant risk to the Sabarmati River, which serves as a vital water source for the surrounding communities.

Despite these orders, the court has expressed dissatisfaction with the pace of progress. The AMC has reported some advancements, such as the establishment of a task force to monitor illegal connections and the initiation of upgrades to existing STPs. However, the court remains concerned that these efforts are insufficient to address the scale of the problem effectively.

The implications of inadequate sewage management extend beyond legal and administrative concerns; they pose significant risks to public health and the environment. The Sabarmati River, once a lifeline for the communities along its banks, has become a repository for untreated waste, leading to the proliferation of waterborne diseases and the degradation of aquatic ecosystems. The contamination of soil and water resources due to industrial effluents further exacerbates the situation, threatening the health of residents and the sustainability of local agriculture.

A Long Wait:

The restraint and patience shown by the courts towards the administrative failure to comply with the orders is telling in the sense that the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti (above), prescribed a timeline ending in 2020 for the government to come up with Treatment infrastructure in the whole of the country.

There is a direction for continuous oversight by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) to implement the Supreme Court judgement. The NGT has also passed orders prescribed for fines on entities releasing pollutants into the river or other waterbodies. However, when it comes to administrative and government inefficiencies, the courts have been far conservative in acting against the non-performing officials and Urban local bodies, as is seen in the case relating to Sabarmati river pollution.

Whether this is a result of judicial restraint or failure to hold the government accountable to ensure implementation, compliance and monitoring, and ensure a hard stop on river pollution, this delay is taking a devastating toll on the life-giving rivers like Sabarmati that have been rendered into vessels to dump sewage and industrial waste. As a result, even these progressive judgments and court initiatives for river conservation are rendered ineffective, with blatant violation and wilful-ignorance of these judgements and norms continuing. How much longer a rope should the courts give the administration, is at the heart of the issue to be debated.

Krishnakant Chauhan is an environmentalist and social activist based in Surat. He is part of Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti and a member of People’s Union of Civil Liberties, Gujarat unit.