Caged birds and prison songs: In chorus, Stan Swamy and the Bhima Koregaon accused kept hope alive

By Vernon Gonsalves

Originally published in Scroll.in.

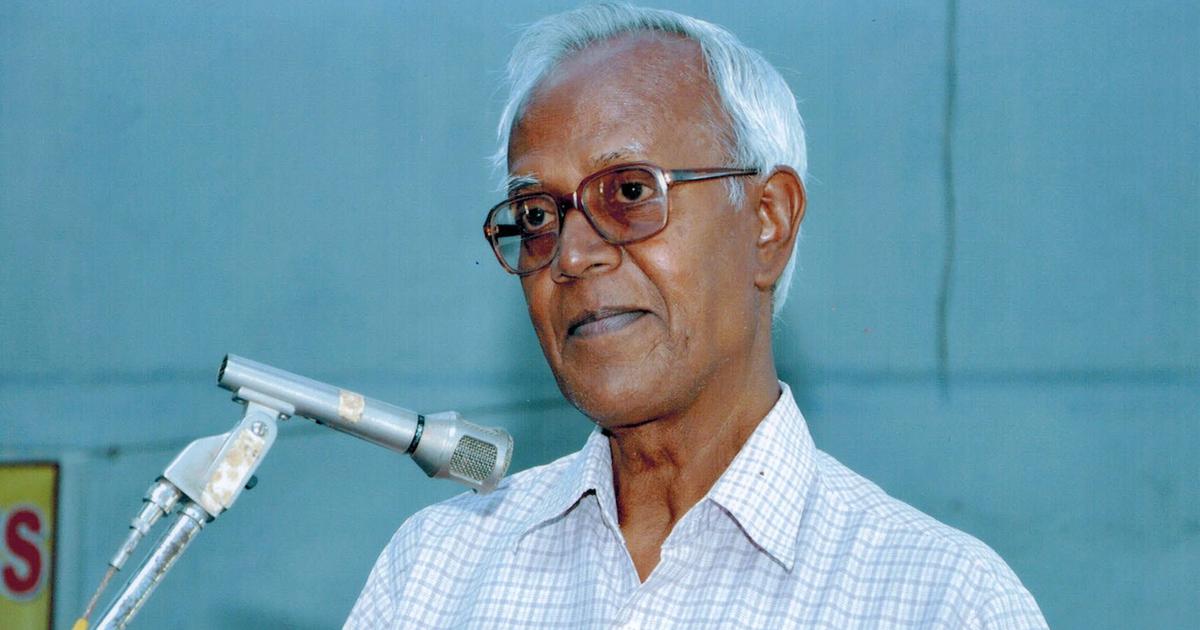

“…I am ready to pay the price, whatever be it. But we will sing in chorus. A caged bird can still sing.”

– Father Stan Swamy

When Stan Swamy, in his last message before landing in Navi Mumbai’s Taloja Central Prison in October 2020, declared that a “caged bird can still sing”, he was not talking about the tunes prisoners sing in jail. He had then not been imprisoned before that and was probably not acquainted with prison-singing in its various forms.

He was actually referring to “a process taking place throughout the country” of dissenters being imprisoned. He was, in a broad philosophical sweep, envisioning the voices of all the oppressed and incarcerated “singing in chorus” against the powers that be.

He, however, also was well aware that the glorious abstraction of the people’s chorus is composed of the very real concrete instances of voices gathering together in small discrete bits and pieces, spread far and wide, wherever they are – in a hit in a remote village, a jhopdaa deep in a city slum or even in a cell in a high security jail.

Soon after coming into prison, Stan started singing – in a literal sense. He was lodged in the prison hospital, which is a warren of small cells and barracks. At that time, another person accused in the Bhima Koregaon case , the poet VV Rao was in a nearby cell. His condition was critical due to two years of prison neglect and Covid. Arun Ferreira and I had been assigned as his carers and were in the same cell. VV could not do things on his own and had to be moved around on a wheelchair.

Stan, who then seemed relatively better off, could walk, though he was a bit unsteady on his feet. So he would regularly visit VV during the times permitted by jail rules. The period post-tea at 3 pm was song time. Stan would come, sit beside VV, and sing at least one or more songs

His repertoire was wide –Jharkhand struggle songs such as Gaanv Chodob Nahin to songs in Tamil, his mother tongue, Paul Robeson tunes to some in Kannada from struggles in and around Bengaluru, where he had been stationed in the 1970s and ’80s. His voice was mellifluous and strong. Each song would be introduced by its background or his association with it or why he wanted to sing it just then. We would join in the chorus. We would imagine our voices wafting past the bars and high prison walls, reaching distant peoples and lands.

The singing was therapeutic for VV, helping his own efforts to rise from the ravages of disease and faulty medical treatment. He’d respond with poetry. Arun and I, enervated and weighed down by the dull and drear of prolonged prison years, would be energised. We would, with renewed vigour, sally into the drudge of ferreting out judicial precedents and jurisprudential logic to tackle the fabrications and falsehoods in our case.

Stan’s singing, however, was a violation of the law. By aiding him with our chorus, we had abetted the crime. Abetment qualifies as an offence in itself.

Singing in prison is an activity proscribed by the Prison Manual – the compendium of rules and regulations that govern jail life.

The very first among the 43 prison offences described and listed at Rule 19 of Chapter XXVI on Prison Discipline of the Maharashtra Prison Manual reads:

“(i) talking when ordered by an officer of the prison to desist, singing, loud laughter and loud talking;”

The eighth in the list is:

“(viii) abetting the commission of any prison offences;”

We thus were prison offenders, who were liable to have a variety of punishments – corporal or otherwise – inflicted on us, as prescribed in the Prisons Act, 1894.

Rule 19 (i) is normally kept dormant. It is imposed very selectively only on certain groups and activities that the administration targets.

Thus, a Nigerian prisoner’s quarrel with an officer, on some personal issue, in one corner of the jail, invited a total ban, throughout the prison, on Sunday morning hymns and prayers – intended as mass punitive action for all African inmates, who are mostly Christian. Meanwhile, though similar tussles aplenty erupt periodically between other prisoners and officers, no collective clampdown on other forms of song has been known to be unleashed.

On the midnight of 13-14 April 2021, when some Dalit prisoners of a particular circle heralded Ambedkar Jayanti with slogan and song, these offenders were soundly thrashed, dispersed and despatched to other parts of the prison. Around the same time, loud midnight celebrations to greet the new-born Lord Krishna did not warrant the same retributive response.

Despite such officerial bias in prohibiting some, while promoting others, the songs of the prisoners themselves co-exist in harmony. The story of the immense variety of jail-singing is a tale in itself. Suffice to say that the crowded night-time locked barrack is the site for many a mehfil, where the suppressed and suffering prison soul finds release and expression.

Those in the two-storeyed high-security Anda Circle, however, cannot gather together. Each is locked away in a separate cage-like cell, walled-off on three sides. These are arrayed in a circular formation divided into a number of “yards” (actually corridors), each cut off from the other in a maze-like structure. A central tower ensures that no cell or its inmate directly faces another. Nevertheless, these bars and boundaries did not stop the singing when many of us accused in the Bhima Koregaon case were shifted there in 2021.

Saturday or Sunday nights would be when the Anda would come alive in song. Gautam Navlakha had a wide repertoire, with a particularly passionate rendering of that timeless authentic paean of hope, Tu Zinda Hai, Tu Zindagi ki Jeet par Yakeen Kar; Shahirs Sagar Gorkhe and Ramesh Gaichor had their own original compositions; Surendra Gadling and Sudhir Dhawale sang songs from Aavhaan Natya Manch and other cultural groups; others – a Bangladeshi migrant, a police inspector, a Muslim accused under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act – would lend their voices.

In the silence of the night, voices from other yards, rebounding through the iron and concrete barriers of the labyrinthian paths of the Anda maze, would sometimes seem faint, as if leaning out to reach across from some distant land. At the same time, the songs from nearby cells – loud, firm and clear – would seem like comrades-in-arms marching together, shoulder to shoulder, to some less dystopic tomorrow. Each cell’s solitariness would seem less menacing and each caged bird would feel less alone.

As we’d hum along, the soul would murmur of what yet may be; and we’d join in chorus with Sagar to say:

“ Your iron bars will melt away

When I sing aloud my songs again”

Then, as his songs rose in crescendo, the heart soared high and reclaimed the land. The caged bird now, not forsaken, not forlorn, could harbour no doubt about what the Shahir foretold:

“Masses will gather, strip conceit and vain,

Bhim battle cries will resound again.”

Sudhir’s words must then strike true, as he, in verse, proclaims:

Consciousness is free

consciousness is transformative

consciousness is guerilla tactics;

crossing the iron bars of the prison

consciousness steps out

as messages, poems, songs of prisoners…

as messages, poems, songs of prisoners…”

Yes Stan, a caged bird can still sing, caged birds still continue to sing, and you, I, all of us, whether in prison or out, will, in chorus sing.