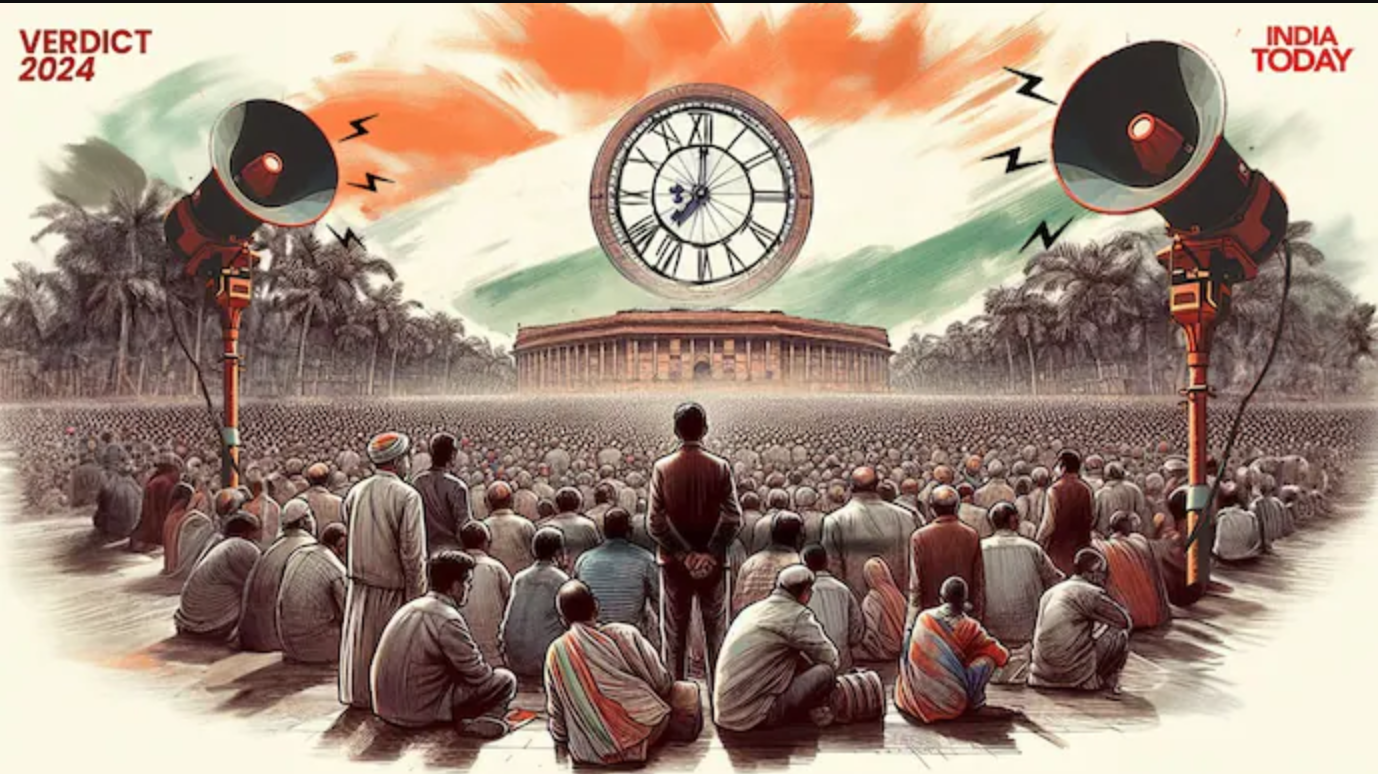

The ECI and the 18th Lok Sabha Elections: Fiercely independent or pliable and unfair?

By PUCL Bulletin Editorial Board

Less than a year back, in 2023, a Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court very powerfully emphasised that elections and adult franchise are part of the basic structure of the Constitution and drew the attention to the cardinal importance of a fiercely independent, honest and fair EC as being at the heart of democracy. The court clearly warned of a situation when a pliable, unfair and biased overseer of the election process, who obliges the powers that be as the surest gateway to acquisition and retention of power.

As the electoral process for electing the 18th Lok Sabha winds down after the massive seven phase election drawn out over 50 days from 19th April to 01st June, 2024, regardless of who the victor is, a major controversy has erupted over the fairness of the electoral process and the role of the Election Commission. Serious questions have been raised as to whether the Election Commission of India has played an independent, non-partisan, honest and fair role and created a level playing field amongst all political parties to campaign within the mandate of rule of law, constitutional values and equality.

We need to take a step back from the heat and bustle of the largest election in world history and examine the manner of functioning of the EC through some events which occurred just before election dates were announced.

The first sign that the 2024 elections may not be the free and fair election which India is used to, came with the passing of the `Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Office and Terms of Office) Act, in December, 2023. This act mandated that both the Chief Election Commissioner as well as the other two Election Commissioners were to be appointed by the President on the advice of a committee consisting of the Prime Minister, Home Minister and the Leader of the Opposition.

What was shocking about this Act was that it brazenly sought to nullify the judgment of the Supreme court in `Anoop Baranwal v Union of India’ (March, 2023) in which the Court had held that appointment of the CEC and the EC’s was to be by the President on the advice of a Committee ‘consisting of the (a) Prime Minister, (b) the Leader of the Opposition of the Lok Sabha, and in case no leader of Opposition is available, the leader of the largest opposition Party in the Lok Sabha in terms of numerical strength, and (c) the Chief Justice of India.’

In an explicit bid to overturn the decision in the Anoop Baranwal case, and so as to solidify executive supremacy in the appointment process of the Election Commissioners, the December, 2023 law, eliminated the role of the Chief Justice in appointing the CEC and EC’s altogether. Even though this was immediately challenged before the Supreme Court, in Jaya Thakur v Union of India, a bench headed by J. Khanna refused to stay the above law noting that, ‘the courts do not, unless eminently necessary to deal with the crisis situation and quell disquiet, keep the statutory provision in abeyance or direct that the same be not made operational’.

The devastating consequences which we are currently experiencing with respect to the compromised functioning of the Election Commission flow from this order of the Supreme Court and the consequent appointment of Gyanesh Kumar and Sukhbir Singh Sandhu as Election Commissioners under the new Act, just two days before the current Lok Sabha elections were to commence.

In fact, all developments since the elections have begun vindicates the prescience of the five judges in the Anoop Baranwal judgment who struck down executive supremacy in appointment of the CEC and EC in March of 2023. In Anoop Baranwal, the Supreme Court seemed to have anticipated, the ‘devastating effect of continuing to leave appointments in sole hands of the Executive’. It held that ‘as long as the party that is voted into power is concerned, there is, not unnaturally a near insatiable quest to continue in the saddle. A pliable Election Commission, an unfair and biased overseer of the foundational exercise of adult franchise, which lies at the heart of democracy, who obliges the powers that be, perhaps offers the surest gateway to acquisition and retention of power.’

The following serious consequences for our right to a free and fair elections have been debated widely by civil society and the independent media.

Firstly, the voter turnout data for the now completed phases of the Lok Sabha 2024 elections for Phases 1, 2, and 3, 4 and 5 has been declared only in percentages as 66.14%, 66.71% and 65.68%, 69.16% and 57.7% respectively. However, actual and absolute numbers of voter turnout of how many votes were polled have not been released, in an unexplained departure from the norm. In previous elections total polling figures were released, so its puzzling that this time around this information is being withheld. It is unfortunate that the Supreme Court, on May 24 adjourned an application seeking directions to the Election Commission of India to publish the booth-wise absolute numbers of voter turnout and upload the Form 17C records of votes polled on its website.

There are also large fluctuation in voter figures, as in Phase 1, the ECI voter turnout estimate as of 7 PM on 19th April was 60% but the updated figure published 11 days later on 30th April was 66.14%, an unexplained jump of 6%. Similarly, for Phase 2, the approximate voter turnout as of 7 pm on 26th April was stated to be 60.96% but was revised to 66.71% by 30th April. The difference between real time data and final figure turns out to be 1.7 crore votes. This difference is unexplained by the ECI. All of this hinders trust in the electoral process.

Secondly, the Election Commission has not ensured that the Model Code of Conduct and the provisions of the Representation of Peoples Act are effectively and impartially implemented to deal with the attempt by candidates to ‘promote feelings of enmity or hatred between different classes of Indians on grounds of religion and language’. Unfortunately, the Prime Minister’ s infamous speech in Banswara where he said that voting for the Congress would mean that ‘Even your mangalsutras will not be safe’ and where he referred to Muslims as ‘infiltrators’, has set the tone for the campaign of the ruling party. The fact that this blatant violation of the RPA and MCC, and which is also a criminal offence under Section153-A of the IPC, has not been responded to effectively by the ECI. The inaction of the Election Commission ignoring scores of complaints being made not just by political parties, but also concerned citizens, has allowed for a deeply divisive, virulent and vituperative campaign which repeatedly trades in tropes of hate. The Prime Minister has brazenly and blatantly violated the Prime Minister’s Oath of Office to ‘bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of India’.

The tone set by the Prime Minister has been followed by other Ministers including Home Minister, Amit Shah, and others in the BJP, which has also violated the constitutional and legal dictum of not ‘promoting feelings of enmity between classes of Indians on grounds of religion’. The ECI has failed to ensure this most basic dimension of a fair election which is based on a constitutional and legal recognition that dividing Indians on the basis of religion is not a legitimate means to get elected.

Thirdly, the question of a free election has also come under a cloud with reports of intimidation, coercion and enticement of candidates into withdrawing their nominations as happened in Surat, Gujarat. On April 22, the last day to withdraw the nominations, the BJP’s Mukesh Dalal was declared elected unopposed from Surat after all other candidates withdrew their nominations. The actions in Surat seem more akin to a tin pot dictatorship than elections in the world’s largest democracy. Similarly, in Indore (MP), the Congress candidate withdrew his nomination after a ‘seventeen-year land dispute was revived with a murder charge added’ according to media reports. This denial of the right to vote to the voters in Surat and the seemingly unconstitutional means used to narrow the choices available to the voter in Indore merits a serious investigation by the ECI. By not conducting an investigation into the above two incidents, the ECI is abdicating its constitutional responsibility for ensuring that India’s elections are both free and fair.

Fourthly, the case of comedian Shyam Rangeela is also instructive of the way the ECI has not performed its constitutional duty. Rangeela, a well-known and talented mimic of Narendra Modi, had decided to contest from Varanasi against the Prime Minister. However, when he went to file his nomination on May 13, he and other aspirants were not allowed to enter the District Magistrate’s office to do so. Finally at 2.58 pm, 2 minutes before the deadline, on May 14, his nomination paper was accepted. He was then told that a required document was missing, which he submitted later that day. He alleges that the RO did not tell him about any other requirement including that of an ‘oath and affirmation’, till his nomination was rejected. The basis of rejection, that the ‘oath and affirmation’ was missing points to the negligence of the Returning Officer. As per the guidelines laid out in the Election Commission of India handbook, ‘it is the responsibility of the Returning Officer to advice the candidate to make the oath immediately after presenting their nomination papers’.

There is no indication that the Returning Officer discharged his duty. If the ECI was serious about ensuring a ‘free and fair election’, it should have intervened in a case which got such wide media publicity and allowed for Rangeela to rectify the defect which may well have happened due to the negligence of its own Returning Officer ! What compounds the suspicion around the working of the Returning Officer is that of the 41 people who had filed nominations, 33 were rejected, leaving Varanasi with its least competitive electoral fray in decades.

Fifthly, there were also shocking media reports coming in of police assaulting voters in polling centres in several Muslim-dominant villages in Asmauli Assembly constituency in Sambhal, UP state. It was alleged by Muslim voters in Sambhal that, about 30-40 police officials got out of nearly 10 SUVs, entered the centre, snatched identity cards and voting slips from the voters and assaulted them with fibre batons and wooden lathis. These are instances of voter intimidation by the state machinery in which the ECI as a constitutional authority should have stepped in to investigate a and take action , but has instead been conspicuously silent.

Civil society as well as the independent media channels has been documenting and reporting the numerous violations of the constitutional mandate of a ‘free and fair election’. The concern of civil society has also been expressed by a spontaneous letter writing and protest campaign titled ‘Grow a spine or resign’ in which postcards were sent to the ECI from across the country demanding that the ECI be held accountable for its action and inactions which have enabled the repeated violations of the Model Code of Conduct and the Representation of Peoples Act, thereby compromising a key element of the basic structure of the Constitution, namely electoral democracy.

However, so far, beyond platitudinal observations, no serious action has been initiated against the Ministers of the ruling BJP party, including the Prime Minister and Home Minister themselves, by launching prosecutions under the Representation of People’s Act and the criminal laws of the land, in particular sec. 153A and 505 IPC amongst other provisions.

What we need to keep in mind is that 97 crore Indian citizens (970 million), constituting 70% of India’s total population of 140 crore Indians (1.4 billion) are eligible voters, participating in the elections now being held simultaneously to 543 Lok Sabha seats. Additionally, simultaneous State Assembly elections are being held for Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Odisha and Sikkim as also 25 Bye-elections to various State Assemblies.

The actions, or rather the inactions, of the ECI are causing the public to mistrust as to whether the 2024 elections are indeed free and fair. It seems clear that whatever the result may be, civil society will have to continue to fight to preserve and defend, a core dimension of India’s identity, that of being the world’s largest democracy.

What is at stake is the very life of constitutional democracy as envisaged by our freedom fighters and constitution drafters, who gifted all citizens universal adult franchise. Our fight, as citizens, will have to continue even after election results are announced – with our primary demand being for an `fiercely independent, competent and fair Election Commission, committed to the rule of law and constitutional values’.