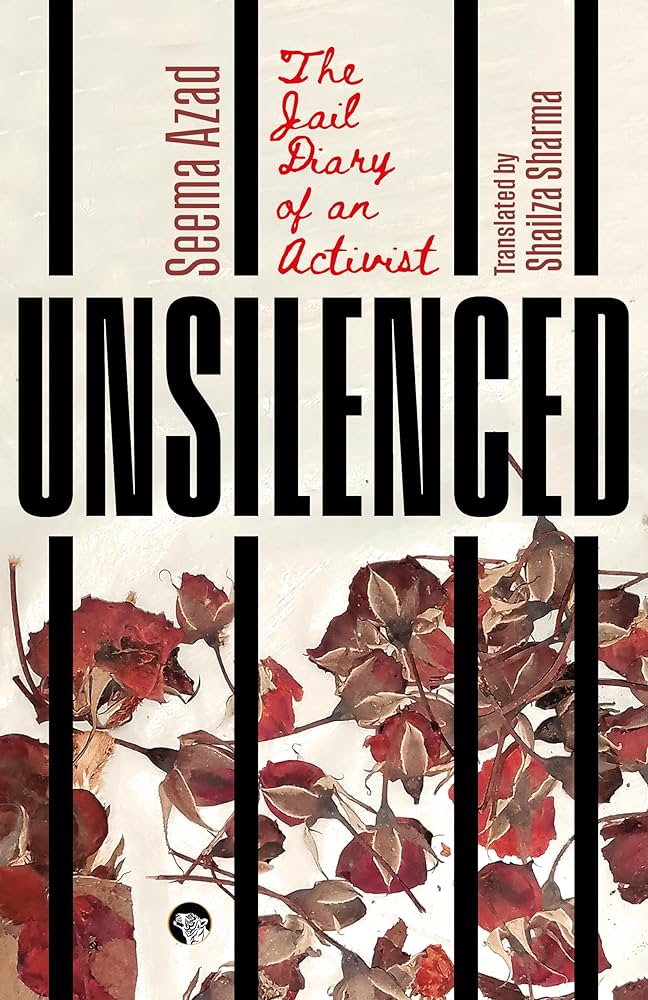

Seema Azad’s “Unsilenced - The Jail Diary of an Activist”

By V. Suresh

Originally published as: “Writing through the Prison Walls”, Frontline, 25th November, 2025

“Zindan Nama: A World without the moon and stars”

Can prison writings make enjoyable reading? How does one turn a grim 2.5 year period spent inside Naini jail (UP) into a riveting account of how children born in prison learn to enjoy the small pleasures of infant games even while they live lives when they don’t know how a star studded sky looks? Of how romance blooms even inside the stone walls enclosing women prisoners, as when a male constable falls in love with a much married poor woman prisoner with 3 children and goes on to marry her after she is released from prison?

Reading through the pages of Seema Azad’s prison memoirs, “Unsilenced – The Jail Diary of an Activist’ (published Aug 2025) one is amazed at the sharpness of detail she brings to her writing. The memoirs are written with a sense of humour, laced with a biting comment about the way social prejudice, caste sentiments, religious practices, cultural superstition and economic deprivation stalk the women prisoners through the high gates of the prison, once they enter it.

Seema’s pen strokes turn stories of women prisoners’ lives, which can ordinarily make for grim, drab and boring reading, into a fascinating journey into the minds and hearts of women undertrial and convict prisoners; offering us an insight into the pettiness and meanness of prison staff and the occasional flash of human feeling they exhibit, as when a prison official arranges for toys for children. We look by, as if we were standing inside the prison, as the women inmates prepare for the mulakaat day – the designated day when they can receive and meet family members, relatives, friends and also sometimes, present and future lovers! We see the excited women prisoners decking themselves with whatever flowers they can collect from inside the prison, oiling and braiding their hair.

Seema’s `Jail Diary’ reflects a wonderful amalgam of her varied persona: Seema the political activist merges with Seema the poet, the humanist, the optimist, the feminist and numerous other things that she strongly believes in. The confluence of the various persona that Seema integrates within herself imbues her writing with a sense of history, politics and human rights written with a depth of sensitivity and humaneness to socio-cultural practices and relations, which stands out in every page of her prison memoirs.

Above everything else, what stands out is Seema the incorrigible romantic.

Incredibly, she and her life partner, Vishwa Vijai, were arrested, remanded, imprisoned, tried and convicted together, in the same case, on the same dates, by the same court on the same accusation! Seema and Vishwa Vijay were arrested together on 06.02.2010 and were in jail throughout the trial as pre-trial bail was refused to both of them. They were both released on bail by a common order of the Allahabad High Court, when they appealed against their conviction. Both of them were released from prison on the same day, 06.08.2012!

Seema and Vishwa Vijai have written their prison memoirs as separate books. While Vishwa Vijay’s book is titled “Hope is not a dead word”, Seema’s memoirs are titled “Unsilenced: The Jail Diary of an Activist”. Together the memoirs constitute a valuable addition to prison literature.

Seema and Vishwa Vijai were arrested by a vengeful state and an immoral police because of their human rights work. They were both prisoners of conscience. Despite the harshness of prison life, and the fact that they are out on bail in their criminal appeal, since their release on 6th August, 2012, both of them have not withdrawn from public activity or standing up for human rights causes. Their courage and determination have only deepened as their voices now also contain personal experiences of the harsh cost to be paid for demanding accountability from the state and the political executive.

Seema, and her partner, Vishwa Vijai are a living testimony of the undying commitment to make our Constitution and democracy work; over the last 10 years since release, their enthusiasm has not dimmed one bit whether it is challenging state terror and police excess, or in support of victims of custodial violence, hate crimes, caste and communal atrocities or environmental challenges.

Reading Seema’s prison diaries reminds one of what Faiz Ahmed Faiz wrote so eloquently while imprisoned (in 1951) in a poem titled, “Let Them Snuff Out the Moon”

“This thought keeps consoling me:

though tyrants may command that lamps be smashed

in rooms where lovers are destined to meet,

they cannot snuff out the moon, so today,

nor tomorrow, no tyranny will succeed,

no poison of torture make me bitter,

if just one evening in prison

can be so strangely sweet,

if just one moment anywhere on this earth”.

Through her writings, and in her life, Seema exemplifies the quintessential human rights warrior – never scared to question those in power and authority. While Seema is a tough person when challenging rights violations, she nevertheless retains a core of caring and compassion. Her concerns cover not just human beings, but also nature, natural resources and the inanimate world too! In her persona, she embodies what Faiz said: that no tyranny and no torture can make her bitter or dim or dullen her commitment to fight for justice, inclusion and dignity.

Seema’s Jail Diary: A Toolkit for the activist!

There are many writing styles that Seema adopts in her prison notebook – which reminds one of Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s famous Zindan Nama – urdu for Prison Chronicles or notebook.

Different readers and professionals will find her writing addressing their interests!

For example, to an ordinary reader, Seema’s “Unsilenced: The Jail Diary of an Activist” is a chronicle of her journey and experiences from the time of arrest by the UP Special Task Force (STF) to being confined in police station lockups during investigation to eventually being imprisoned in Naini Central jail during the course of trial and conviction.

The feminist, the gender and women’s rights activists will find a sensitivity to women’s issues which are normally not found in prison literature, which are mostly written by men. Seema points out that the bulk of women confined to prison come from socially and economically marginalised and discriminated communities. Their harsh conditions of living in ordinary life are mirrored in their disempowerment when kept in custody.

For those coming from the field of `Prison Sociology’ the book is rich in information, contains highly nuanced comments about the interplay of caste, class, community and literacy background of the women inmates, seen from the lens of a woman activist – prisoner.

The Jail Diary is however unique in one respect, which also stands out in comparison with many other similar prison accounts. This difference lies in the clever inter-weaving into the textual narrative of the book, ways and methods to be adopted by anyone unfortunate to be arrested by the police, to safeguard and assert their fundamental rights guaranteed by the Indian Constitution.

Any arrest by the police and subsequent confinement is always a traumatic and unnerving experience. More so, when the arrest is totally unanticipated and sudden. The experience is made more difficult when the arresting police do not inform the arrested person why they are arresting them, about the case against them and other details. In Seema and Vishwa Vijai’s case they were arrested by the UP Special Task Force, a specialist police force given vast powers and resources to arrest people for `so called’ “Special Crimes”.

It is very natural and understandable for the person arrested without warning to be emotionally and psychologically `psyched’ out. Apart from the questions abounding about the arrest itself, many other concerns flood the mind: how do we inform the family members? How will they take the arrest? What about contacting a good lawyer of your choice to come over to the police station? How to inform other human rights activists that your sudden disappearance was because of police arrest; and that they should immediately inquire from the police authorities why the activists were arrested. The fear always lurks behind the mind, especially when the arrest is politically motivated, about whether the police will kill you in a staged encounter.

The importance of not allowing anxieties and tension to overrun our sensibilities thereby increasing mental stress, is pointed out in an incident that occurred soon after she and Vishwa Vijai were arrested. In a very matter-of-fact way Seema describes how soon after her arrest she was locked up in a dark room in the police lock up. The room was filthy with uncleaned, stinking toilets. She could find a place to rest only by following the contours of the wall. The only source of light in the totally darkened room was a small sliver of moon light shining through a slit not even half an inch in diameter. As she battled inside herself not to allow her mind to be frightened and panic she remembered the poetry of Pash:

“This tiny sliver of blue sky,

Is my life line,

Bearing the weight of the heavens on its shoulders,

It saunters by”.

Recollecting the song stopped the feeling of terror overtaking her. Seema describes it eloquently, “The moment I remembered this poem, my thought process changed course. I began thinking of all the revolutionaries who had not broken down even in the face of utmost atrocities. I thought of Nazim Hikmat, who was regularly coerced to stand in a mass of sewage. The foul smell would give him headaches. He would start singing loudly to avoid letting his enemies see him in such a condition, who were waiting to take pleasure in his misery”.

This is an important reflection for rights activists of all shades. It is well known that with the police, the most difficult experience is not just the physical torture but the mental and emotional pressure they pile up. At the end of the day it’s all about mental games. The stronger the arrested person remains, the less it is possible to crush the spirit of the activist.

Throughout the memoir Seema writes about the practical skills and legal knowledge that all activists in particular, and citizens generally, need to have. Do we have a right to demand the grounds we are arrested in or in which case? Do we have the right to contact our family members and personal lawyers? Can the police deny us this right? What tricks do the police play to ensure that the arrested person is not able to reach out to family and lawyers? Can the arrested person complain of physical and emotional torture during interrogation while in custody? What about registering a complaint of illegal arrest and confinement the very first time the arrested person is produced before a Magistrate for remand?

The memoirs contain many references in which her prior knowledge about legal procedures and protection helped her to inform her parents, siblings, media professionals and lawyers. In this sense the Zindan Nama is an invaluable tool kit of sorts, for current and future activists.

Duplicity of the police and the deviousness of the media: Concoction to repress

Seema’s memoirs documents the innumerable ways by which the police brazenly abuse their powers to subvert important legal rights, starting from the responsibility vested in the police to inform the person they are arresting about the grounds for arrest, details of the case, intimation to near family members, being informed of their right to call a lawyer of their choice and so on. These rights which were explained in the landmark SC case of `DK Basu vs State of West Bengal’ (1997). The ruling commonly referred to as the DK Basu Guidelines or the `Commandments to the police’ eventually got incorporated in criminal law by inclusion of section 41A of the Code of Criminal Procedure. The SC guidelines were meant to operate as a vital `check and balance’ to legitimate exercise of power by the police while preserving the rights of arrested persons.

In the case of the arrest of Seema and Vishwa Vijai, the UP STF brazenly violated all the requirements in law to inform the arrested person and a close relative of why they were being arrested or where they were going to be detained and so on. All through the arrest, interrogation, remand and investigation the police are recorded to have behaved as though they were a force above and beyond the law of the land. Unfortunately, despite voluminous evidence available from across India, the judiciary, at all levels, do not respond to complaints of abuse of law allowing the police to get away with impunity, even when they commit egregious violations of the law.

The deviousness of the police is matched by the extent to which the state and police go to orchestrate a media circus around the arrest of political activists like Seema and Vishwa Vijai, whipping up popular opinion and wrath against them as being `antinational’, `dangerous extremists, naxals, Maoists’ and dreaded criminals is written in a personally poignant manner. She writes with severity about the servile manner by which select newspaper journalists report their arrest with totally false information. These journalists are given access to select documents, concocted in the first place by the police themselves, to ensure that public opinion is prejudiced from the beginning. The effect of such vile tricks played by the cops follows Seema throughout her stay in Naini Central Prison. For example, well into her stay in Naini, she is asked by some prison guards who a “Maoist” is and whether she is a terrorist!

What is striking in her approach is that she never lost an opportunity, whenever it presented itself, from clarifying to anyone asking for the reasons for their arrest, the true character of the police. How they foist false cases against activists; cook up fabricated criminal cases; have no hesitation to plant false evidence in the homes and properties of arrested persons, threaten and intimidate family members and who use their position and power to take sides with the rich, propertied and the politicians. No person is too small, no opinion is too insignificant to clarify, explain, deconstruct the way the state, political executive and the police operate, about the importance of using every occasion to deepen human rights consciousness.

In that sense “Unsilenced: The Jail Diary of an Activist” is a treasure house of `SURVIVAL TOOLKITS’ which every activist should read.

“Patriarchy, women and life in prisons”

In a very moving part of the memoirs, Seema recounts a statement made by a jail official when she is brought to the Naini central jail and tries to sit on a stool instead of crouching on the ground:

“Beta, you cannot sit on a stool anymore; you’ve lost the right; you will have to sit on the ground” –

The statement poignantly captures the harshness of the introduction to prison life. The arrested person is no longer a human being; she cannot claim to have any right to be treated with kindness, humaneness or concern. She is now only a cipher, with a number for her name, to identify herself.

The robbing of inherent dignity of being a woman is shown in numerous ways, to have a numbing effect on the self-esteem, self-respect and confidence of the women prisoners. The women prison officials, women staff, convict prisoners who are used by the prison department as supervisors of other prisoners – all of them indicate the same expression of male, patriarchal values and mind sets. There is no show of concern, sensitivity or caring – even at minimal levels – within the prison system. Abusive language, using force including physical violence, punishing inmates for the slightest transgression of rules – become potent weapons in the hands of prison officials. They are used to keep the inmates under constant sense of fear and subordination; by continually creating a sense of indignity, powerlessness and loss of self-esteem, the prison system ensures that women inmates remain as mute residents, unable to exercise their `agency’ to challenge unfair rules and extraction by prison officials.

Jahnavi Sen in an article titled, “Buzz of a mosquito … but with the sound of Grief, The Lives of India’s Women Prisoner’s” writes about what some inmates of a Mumbai prison told her:

“Every time we get back from one of our court dates,” Meena says, “we had to strip completely in front of the women guards, and they would put their hands everywhere you can think of. And there’s nothing you can do. You feel completely powerless.”

“It didn’t even matter if women were on their period,” Leela says. “They would be asked to take off their underwear, to spread their legs.”

In a dairy entry dated 21st August, 2011 Seema writes, “I am pained to see that women in prison do not possess any feelings of self-respect … Women in prisons engage in petty quarrels with each other, but they do flinch or even protest when they are abused and humiliated by the Constables. Instead they prefer to indulge in their adulation. Seeing this, I wonder how long it would take for democracy to seep into our society when half of our population has not even been able to develop dignity for themselves” (added emphasis)

“Cycle of Looting”: Institutionalisation of Corruption

Even though the widespread prevalence of corruption in prisons, across India, is well documented and known, Seema, in her very dramatic style highlights how corruption is not just deeply entrenched but is also very scientifically constructed!

The scene is the visit of Seema’s sister’s visit to meet her bringing peeled peas. On that day, a much dreaded women official, Mithilesh Pandey had returned to work after availing leave. Seema had instructed her family members only to bring what were permitted food items. She later came to know that jail officials permitted non-permitted food stuff, including fully cooked food to be brought in, of course for a price.

The trick was that the police staff outside the prison would demand only a small sum at the outer gate. Anxious to somehow reach food stuff, relatives paid up. Once let in, the visitors had to pass 2 to 3 other locked gates to finally enter the prison meeting place. The bribe amount to be paid to the prison officials kept going up at every gate and by the time the visitor got to the final door they would have paid a hefty sum which would be divided amongst the prison staff. Having paid to enter with the food stuff, visitors would not fight or object to extraction of more money to somehow reach the food stuff inside.

Referring to this as “the cycle of loot”, Seema highlights the institutionalized manner in which corruption is laid down in the prison. The irony is that everyone knows about this: but no one, literally no one, is bothered to do anything about it: none from the State prison department or the state police or even the judiciary feel it’s important to check corruption as it ultimately affects the poorest sections of women, who go to jail. This is the tragedy of prison life for all in general, and for women prisoners, in particular.

Caste & Community: Superstition and Prejudice

Seema points out that by and large bulk of women prisoners in jail belong to the OBC communities, Dalits and Muslim communities. Women belonging to the `Pardhi’ community – previously known as `Denotified Community or Criminal Tribes” were also regularly arrested for petty thefts and smaller offences if they had taken place in the areas under the jurisdiction of the local police stations.

One thing common to the women prisoners irrespective of the caste or community of the prisoners was the constant recourse to superstitious beliefs especially of `Spirit Possession’. In a fairly longish recording of events in the prison when she observed different women inmates acting as though they were `possessed’ Seema records the dilemma of approaching superstitious practices from a `rational, scientific, objective and factual framework’. As she records, “I remain cautious about these matters and do not say anything because I fear that if I said anything, people would forget the goddess and attack me instead”.

A number of incidents are narrated to highlight how people from differing social backgrounds claim the use of magical chants, mantras and spells can help detect theft inside the prison barracks or the ability to influence officials, including judicial officers and more bizarre claims. Irrespective of the outlandish claims, this only indicates the wider social consciousness prevalent in society which believes in spells, mantras and magic potions.

There are two limitations to any remedial action to check the play of superstitious beliefs inside jails: first, the specific instances of superstitious acts and how widespread is its prevalence, can be found out only by a person who is an inmate in the prison and has watched these incidents; few outsiders will be given privy to these incidents; second, is it intervene when incidents as picturised by Seema occurs. For which the prison staff will need to be trained.

Seema writes that Vishwa Vijai also told her that similar beliefs and practices are prevalent in the men’s prisons also. So it is not peculiar about women’s prisons and will need to be studied better with the help of psychiatrists, psycho-analysts, counselors, social workers and other specialists.

The problem here is that the prison officials themselves, many times, exhibit similar superstitious beliefs!! So the change has to start from them!

The colourful world of children born in the dreary world of the prison

The most poignant portion of the Zindan Nama is the section where Seema writes about the lives of infants and children born when their mothers were in prison or brought along with the mothers at the time of imprisonment.

The most touching scene is recounted about an evening incident when Khushi, a small girl born in prison, came running in excitement to Seema pointing to the skyline where the moon could be seen rising. She was wanting to know what it the shining object was. Her mother explained that she had never ever seen the moon before as everyone was locked up at sunset and do not even see or sight the moon. Seema puts it very movingly pointing out, “I could not even fathom that the joys of expressing wonder over celestial bodies could be snatched away from any child; that the twinkling stars that put them to sleep can be plucked from their imagination”. The formative insights of young children built around first hand experience with nature was deprived to children who remained with their mothers until they became 6 years old after which they were taken away from the custody of women prisoners. Seema points out wistfully, “ .. many formative experiences and significant needs are neglected in their upbringing, which can no longer be fulfilled by anyone in their entire lifetime”.

A number of recent articles also highlight the plight of children who are forced, due to circumstances, to remain in prison with their mothers. It’s a poor reflection on both the prison department and state policy as also the apathy of wider civil society that they continue to remain blind, deaf and apathetic to the plight of children inside jail.

It’s a shame on a country which aspires to be a leader in the 21st century world, that they do not give priority to ensuring that facilities are created for children of women prisoners so they do not lose their childhoods.

Seema Azad’s “Unsilenced: The Jail Diary of an Activist” is a valuable addition to the field of prison studies. Future rights activists, academics, policy makers, members of the judicial fraternity and the media community will all find numerous issues which Seema has skillfully described in her prison memoirs. Although written a decade back, the issues she highlights are as alive today, as they were during the 2.5 years she spent in Naini prison.

This grim reality is borne out in the findings of an official report titled, “Women in Prisons, India’ brought out by the Union Ministry of Women and Children, Government of India, in 2018 which pointed out:

- “There are a number of provisions in the form of laws, rules and guidelines that protect women from exploitation in prison and guarantee them basic services. However, the implementation of these provisions is found to be largely lacking and women face a variety of problems while living in prison”.

- “Women are entitled to have access to education while in prison, but apart from provisions for basic literacy, educational facilities are largely missing. Skilling and vocational training is also considered an important part of reformation, and every prison is meant to provide these services. Efforts in this regard are largely eye wash, with most courses imparting skills that are unmarketable, financially unviable and thus not much use to women after release”.

- “Physical and sexual violence is a common scenario in prisons, faced by inmates at the hands of authorities and other prisoners. The provisions for ensuring safety of women in prison and addressing their complaints need to be followed strictly, which is not the case currently”.

What is striking is that even an official report of the Union Ministry of Women and Children has not minced words in laying bare the real pathetic and unacceptable situation prevailing in women prisons throughout India. Seema Azad has flagged numerous other issues in her prison memoirs, all of which requires immediate attention from the variety of state agencies involved as also academicians, policy makers, media, women’s rights, prison’s rights and human rights groups.

Seema Azad’s “Unsilenced: The Jail Diary of an Activist” is a delightful read. Apart from chronicling her encounters with both the police and prison departments, she writes in an exuberant, engaging manner what life for a woman activist means in captivity. Though spending 2.5 years in captivity, denied the luxuries and liberties of the ordinary citizen would not have been easy she writes with a sense of hope, with optimism.

Reading Seema’s work reminds me about the poem, “To Althea from Prison” written by Richard Lovelace who was imprisoned as a political prisoner in 1642.

“Stone walls do not a prison make,

Nor iron bars a cage:

Minds innocent and quiet take

That for an hermitage.

If I have freedom in my love,

And in my soul am free,

Angels alone, that soar above,

Enjoy such liberty”.

Seema’s romance is not just personal! Her’s is a romance with the ideal of `democracy’ – of dignity and fraternity, of equality and equity, of fairness and justice. As someone who has dedicated her life to the ideal of creating a caring, humane, egalitarian and compassionate society she has brought to her Zindan Nama, the exuberance of an idealist: As Mahatma Gandhi is reported to have aid, “What does it matter if the world calls you a dreamer?” For it is dreamers who have changed the world!!

I hope that Seema Azad’s `Zindan Name: The world without the moon and stars” will be translated into other Indian languages so that more people can read it and take courage from it. I also hope that the book becomes a prescribed text book in universities for courses in law, criminology and correctional administration, prison studies, social work and other faculties who have anything to do with prison studies. Very importantly the book should be circulated amongst judicial academies so judicial officers too can read the book and discover how they can use the judicial mechanism to humanise and democratise our prisons. That will be the most fitting tribute that can be made to the thousands of women prisoners who have gone through the prison system in India.