PUCL Dialogues (VII) - India’s Role in the Human Rights Council: Is there a constitutional vision in India's foreign policy

Relevant State

Click here to see the full recording of the discussion.

India’s Role in the Human Rights Council

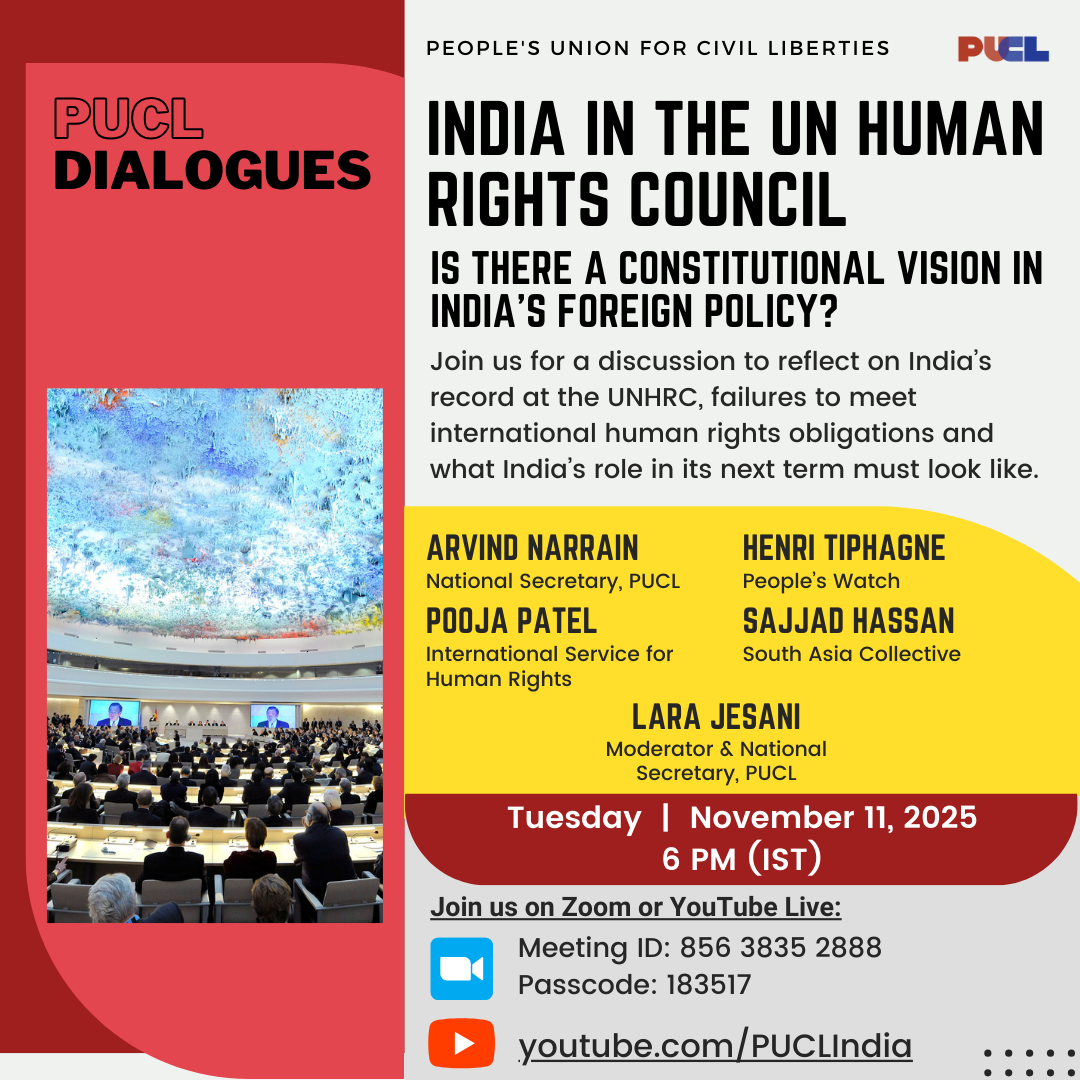

The session of the PUCL dialogue organized on the 11th November, 2025 was moderated by Lara Jesani (National Secretary, PUCL), and the speakers were Henri Tiphagne (People’s Watch), Arvind Narrain (National Secretary, PUCL), Pooja Patel (Deputy Director, International Service for Human Rights) and Sajjad Hassan (South Asia Collective). Here is a summary of the discussion that took place:

Introduction

Recently, India was one of the 14 member-states elected to the UN Human Rights Council. The Human Rights Council(HRC) is an intergovernmental body within the UN, comprising 47 member-states, whose mandate is to promote and protect human rights across the world.

India’s membership of the HRC is critical as there have been growing concerns around human rights in our country, right from the SIR process which will disenfranchise our citizens to increase in hate crimes against Muslims to the dismantling of constitutional rights, especially freedoms guaranteed under Article 19, including the right to protest, right to association and the right to freedom of speech and expression. It is in this context that we felt we should reflect on the election of India to the HRC, what its performance has been so far, and what should India do on the HRC.

Arvind Narrain: Constitutional vision in India’s foreign policy

I want to reflect on why as Indians, we do not engage much in the question of what is going on in the Human Rights Council or the General Assembly. Amartya Sen pointed out that India is the size of a continent, and therefore, our concerns end up invariably being inward. There is so much going on within the country, that we often do not pay attention to what is going on outside. This discussion is really an effort on our part to say that it is very important to know what is going on in terms of our foreign policy. I recently read Mr. Jaishankar’s (Minister of External Affairs) book, called ‘The India Way’. The book gives us the sense that as far as Mr. Jaishankar is concerned, for him foreign policy is defined ‘contemporary pragmatism’, by which he means that there is no larger vision or larger framework within which foreign policy is governed, and our relationship with other countries is purely transactional.

The problems with this approach according to Pratap Bhanu Mehta, is that if you want to build a larger coalition at an international level you have to do it around some issue or certain values. If you don’t stand for anything other than your own self interest, nobody’s going to stand with you. If your only interest is self-interest, it’s actually against your self-interest because you can’t get people together. In the past, we had a vision, whether it was the non-aligned movement or the idea of India standing for the global South, that vision is absent today.

There should be a vision and that vision should derive from the Indian constitution. Just as we hold the Indian government accountable for its violations of the Indian constitution within the country, we should hold India accountable for not standing up for the values of the constitution in international forums as well.

In the HRC, India’s voting and what India does should be structured by the framework of the Indian constitution. For example, with respect to civil and political rights, the Constitution is very clear, as we recognize the right to freedom of speech, the right to association and the right to assembly. And therefore, how does India respond to these issues at an international level? To give one very specific example, when the UN mandate of the Human Rights Defenders came up for renewal, there were a number of hostile resolutions which were moved by various authoritarian states right from China to Egypt to Saudi Arabia; all of which sought to dilute the mandate of human rights defenders.

India joined these efforts to dilute the mandate of the human rights defenders. Finally, of course, when the writing was clear, India voted for the resolution. India’s efforts has always been to dilute the mandate of civil and political rights. This is completely contrary to the mandate of the Indian constitution. Therefore, the Indian government should be held to account for its votes and participation in the Human Rights Council. Another example relates to country-specific resolutions, when we look at grave human rights violations within the case of one particular country. For instance, in the case of Syria, even when it came to the condemnation of the gravest human rights violations such as the use of Chlorine gas or the use of chemical weapons or the strong condemnation of the Syrian government’s attacks against medical facilities, personnel and vehicles India’s position was abstention. Why do we abstain? We need to start asking the Indian state these questions, as to how they are taking forward the values and vision of the constitution at the level of the Human Rights Council.

In the case of Palestine, we have 4 very remarkable reports by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Occupied Palestinian Territories. All 4 reports make the very important case that what is happening in Gaza is within the legal definition and understanding of genocide. As per the Genocide Convention which India has ratified, the obligation is to prevent and punish the crime of genocide. The question to the Indian state therefore is, if your self-assumed obligation is to prevent and punish genocide, what have you done to take that obligation forward? We have done absolutely nothing.

A counter-example which we have to give, is a country which tries to work within the framework of its constitutional mandate, when it comes to the question of foreign policy is South Africa. I’m sure colleagues and friends in South Africa might have levels of disagreement but the broad point is that South Africa feels impelled to fulfill its obligations to ensure that international law is respected. This comes through with the fact that South Africa has filed a case before the ICJ against Israel, making the case that what Israel is committing in Gaza is a genocide.

Why is India silent? One answer is also that as civil society we have not put enough pressure upon the Indian government to demand that it fulfills its obligations under both the Genocide Convention and the obligations which are pointed out by the Special Rapporteur.

The next point I want to make is the entire framework of LGBT rights. At one point, when India was asked whether it would support the mandate of the Independent Expert on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, its position was that India cannot take such a position, because of a case going on in the Supreme Court. Even post-decriminalization, India has not voted to support the mandate of the IE on SOGI.

This is a shocking abdication of its constitutional obligation. When the court is saying we are in support of LGBTQ rights, and interpreting the constitution to say that the right of privacy and dignity of the LGBTQ people are recognized, the Indian government still abstained.

Therefore, the point I am making is that India’s voting as far as the Human Rights Council, has been to either dilute human rights standards or simply remain silent on them.

The final point I want to make is if we try and think of a deeper rooting in the constitution, of what our values should be, we’ll have to go back in time. Interestingly enough, the person who took us back in time is the current mayor-elect in in New York, Zohran Mamdani. He invoked Nehru’s speech, A Tryst with Destiny, where he quoted Nehru saying ‘a moment comes but rarely in history when we step out from the old to the new when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation long suppressed finds utterance.’ It is interesting that the next line is ‘it is fitting that at the solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and our people into the still larger cause for humanity.’

When the flag resolution was moved in the constituent assembly, Nehru said, “This flag that I have the honor to present to you is not a hope and trust, a flag of an empire, a flag of imperialism, a flag of domination of anybody, but a flag of freedom not only for ourselves but a symbol of freedom to all people who may see it.”

There is a larger vision which underlines the drafting of the Indian constitution itself, and a broader understanding of what freedom means – freedom is not just for us, but for people around the world.

The other constitutional roots which should structure our foreign policy is the Directive Principles of State Policy, under Article 51, which says ‘the state shall endeavor to: (a) promote international peace and security, (b) maintain just and honorable relations between nations, and (c) foster respect for international law and treaty obligations in the dealing of organized people with one another.’ Under Article 51(c), we have the basis to make the case that we have the obligation to prevent and punish the crime of genocide and we should be standing with South Africa in the ICJ.

So we have to get past the historical amnesia and rediscover our constitutional rootings in the way we conduct our foreign policy.

But what I am saying is not abstract, when we look at India’s voluntary pledges put forward in the run up to its election to the Human Rights Council for 2026-2028. India says, “India’s commitment to human rights is deeply rooted in its constitutional framework which guarantees the fundamental rights of its citizens and promotes the ideals of justice, liberty and equality. This candidature for the HRC is a reflection of India’s dedication to advancing the principles of human rights globally, fostering dialogue and bridging divides to achieve collective progress…’

So, we have to ensure that India functions both in tune with its constitutional values and its pledges. We need to assert to the Indian state that it must fulfill its self-declared mandate in its next term.

Henri Tiphagne: The downgrading of the NHRC

One of the subjects I was asked to speak about was the National Human Rights Institutions. All of us know that we have over 9 National Human Rights Institutions with powers to handle complaints. Every state has commissions which are known as state human rights institutions. In total, there are about 170 such institutions across India. No other country globally has so many institutions. And therefore, we have every right to ensure that our institutions are effective. In order to do that, all NHRIs come under a global initiative called the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions. This is the body which accredits the NHRIs on the basis of whether they adhere to the Paris Principles, and grants them the appropriate status. India’s NHRC was accredited A grade in 2011, with a question mark which was removed thereafter. In 2016, it was deferred by a year, and India was told that it cannot be granted A grade. In 2017, they were once again granted an A grade. It was deferred in 2023 and 2024, and was finally downgraded in 2025. India has filed a review application which is pending, which will be resolved in November or early December. Why is this important?

Because this process of accreditation brings up a few issues which are known to all of us. One is the involvement of police officers in investigation of complaints. Second is the composition and the lack of pluralism in this commission. Third, the whole selection process is against the Paris Principles. The appointment of the Secretary General himself is a person from the Prime Minister’s office. The appointment is supposed to be independent. Fourth, the NHRC’s cooperation with human rights bodies. And finally, how are they addressing human rights issues. These are the issues based on which the NHRC has been evaluated. It has been pointed out repeatedly, that the NHRC is not fit to be granted an A grade status at all.

A recent report by ANNI, the Asian NGO Network on National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs), has also rated them based on a large exercise, in which many of you participated. It is the response of civil society which resulted in India being ranked 10th among 11 countries with a rating of five points, when the maximum point of other countries was 9.75. On themes such as pluralism, promotion and protection and in terms of cross-country issues, we were ranked 11th, the last. It is a shame for the NHRC that its civil society rated it so badly.

We have a number of vacancies that still continue in the NHRC. It is important to read the last Sub Committee on Accreditation (SCA) report, from which I will share one paragraph alone. “The SCA also notes attempts by the Indian national authorities to engage members

of the SCA related to the accreditation process of the NHRC including the involvement of various foreign missions. The FCA emphasizes that the GANHRI accreditation system is a peer review process which requires NHRIs to maintain their independence.” Friends, this is the level that our NHRC, our foreign missions have stooped to ensure that some sort of political pressure is being put. They did it in the past, and now it is on record.

All this has happened not because of Indian civil society alone. I want to acknowledge particularly the participation of ISHR with Pooja Patel, who is one among many other international human rights organizations which also participated in this process of monitoring and speaking aloud in terms of the NHRC and its performance. It was regional human rights organizations as well as international human rights organizations.

The cost of doing this is the various other reprisals that we have faced here. But we will continue unitedly because we know that the NHRC belongs to us and we need to continue to remind the Indian government of their own voluntary pledges.

Another recommendation I want to make here is that we must ask parliamentarians to join this entire drive. Let it not be only civil society, human rights organizations led initiative. Let more and more parliamentarians join the drive.

Pooja Patel: India’s performance in the Human Rights Council

As the previous speakers have already mentioned the membership to the human rights council is not just a seat with a vote. It is also a responsibility to uphold the highest human rights standards both internationally and at home.

Firstly, when it comes to UN calls for action this criterion was met. There were clear UN level calls for action. The Secretary General, the High Commissioner for human rights, several UN experts had repeatedly raised concerns about Kashmir, the CAA, Manipur, restrictions on civic freedoms, situation of minorities etc. Dozens of UN special rapporteurs have urged the HRC to act especially when it comes to freedom of assembly, religious discrimination, detentions under national security laws including of human rights defenders and journalists.

There’s also a criterion about the degree to which the state has acknowledged the human rights challenges, that it faces – noting that no state is perfect. There are human rights concerns in every country in the world. But what is the level of commitment that a state is taking on its own initiative to try to address these challenges. On this we found that this criteria has also not been met. India has rarely admitted to systemic human rights problems. Instead, it often describes UN criticism as biased or politically motivated. Responses on specific HRD cases is often to cite rather the responsibilities and obligations that citizens have to uphold the law.

When it comes to engagement with the HRC and Special Procedures – while India does participate in the debates, it has delayed or denied country visits by Special Rapporteurs and rejected many important recommendations as well.

When it comes to the access for media, NGOs and defenders, civic space has shrunk, journalists face criminal charges, NGOs face funding blocks etc. So, we consider that that criterion also has not been met.

So overall, India shows procedural cooperation but lacks substantive openness. It engages formally but not in spirit. Accountability and transparency are often absent.

At the HRC, India has positioned itself as a defender of sovereignty and dialogue rather than as a promoter of human rights accountability. It sees itself very much as a counter geopolitical balance to the west. However, at the same time, because India values maintaining its own autonomy and flexibility, the concept of alliance is also a bit limited. It doesn’t have kind of a strict alliance, but we do see patterns of convergence with other states, especially those who emphasize sovereignty, non-inference, global south solidarity, and also those who align on restrictions to civic space.

It often abstains or votes cautiously on country specific resolutions arguing that human rights should be addressed through cooperation and not confrontation. We also find that it takes a much more pragmatic line rather than principled.

In terms of what other member and observer states have said about the situation in India in the HRC, we found that in recent years, relatively few states at the council have been

willing to subject India’s human rights record to sustained and meaningful scrutiny despite major domestic concerns. A significant factor shaping this hesitancy is probably the primacy that many states are placing on maintaining strong bilateral and strategic relations with India, especially in areas of trade, security, and regional influence.

At the same time, India has consistent consistently responded forcefully and negatively to external criticism, framing scrutiny as politically motivated or as an infringement on sovereignty. This combination of diplomatic caution by other states and India’s defensiveness has limited robust multilateral accountability and so it has allowed significant human rights concerns to remain insufficiently addressed on the international stage.

I just want to turn now to India’s upcoming term because I want to situate the next six years within the geopolitical and funding context in which we currently are. The upcoming term comes at a particular moment for the UN system and for human rights multilateralism in general. I’m sure you all know that the UN system is facing deep budgetary strain. We’re talking of spending cuts of about 20% for 2026 and beyond. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights warns of a shortfall of around $60 million. What does this mean? It means that the capacity of the human rights council, of treaty bodies, of special procedures to respond robustly is under pressure and will be under pressure in the foreseeable future.

I think that we have a number of learnings from the previous membership term that we also have to account for. We categorize these sometimes as risks and challenges. India’s record suggests a lack of principled engagement including on restricting NGO participation at the UN through obstructing accreditation processes for example as well as you know a pattern of reprisals against human rights defenders who want to engage with the system.

Despite these concerns India’s HRC membership may offer some strategic openings through resolutions, through Special Rapporteur reports, through statements, and other thematic initiatives.

Therefore, I have four main recommendations going forward. First of all, my first one is to strengthen the exchange between international NGOs and groups inside of the country as well, and perhaps to systematize some of this work through maybe a joint civil society strategy group that monitors India’s engagement at the HRC. This will help identify opportunistic moments and can coordinate advocacy as well.

Secondly, to map opportunities where UN outcomes can be translated into domestic leverage for policy or public engagement. There is absolutely an implementation gap. But I think what we have to maybe do is an assessment of the outcomes that have come out of the UN and how they can be taken forward in tactical ways.

Thirdly, to develop a rapid response mechanism to address emergency and urgent situations as well as attempts to obstruct NGO participation or retaliatory actions against human rights defenders engaging with the UN.

Finally, to prioritize engagement that both pressures India to adhere to its international obligations and identifies achievable entry points for positive outcomes in domestic human rights practices. For example, we could consider a set of very minimum benchmarks that India must achieve in the next six years.

India’s return to the council in 2026 is a test of credibility. If India wants to lead globally, it must also listen, reform, respect rights at home. And it is up to us as a human rights community to ensure that this term is remembered not just for diplomacy but also for real human rights change.

Sajjad Hassan: India’s engagement with UN human rights mechanisms

Now for a country which is the most populous country in the world, the largest democracy in the world, not to have a human rights office and yet to claim it’s constructively engaging with UN and human rights is a big red flag.

As a result, on occasions when the High Commissioner raises concerns about what is happening in India, there’s push back. For instance, in March 2025, the global overview is delivered by the High Commissioner where he talks about the human rights situation in different countries. He referenced the situation in India and issued warnings against targeting journalists and civil society members and also mentioned the violence and abuses in Manipur and Kashmir. What resulted was that India called these remarks ‘unfounded and baseless.

This is the pattern we’ve seen for several years now, that when UN actors including the High Commissioner raise these concerns, there’s a rejection of these concerns mostly framing them as misinformed, biased, inconsistent with reality etc. There’s no engagement either with facts or with plans to improve things or even to have an honest dialogue.

One of the instruments that HRC members have is the UPR, the universal periodic review, which is a peer-review of countries human rights record and happens every five years. The last one which was the fourth cycle happened in late 2022. A report by Human Rights Watch said that there were serious concerns raised in India’s UPR. In this review 130 member states made 339 recommendations. 21 countries urged India to improve its protection of freedom of religion and rights of religious minorities. 20 countries said that India should improve protection of freedom of expression and assembly and create an enabling environment for civil society groups, human rights defenders and media to do their work. 19 countries said that India should ratify the Convention against Torture, the refugee convention, Rome statute also withdraw AFSPA and UAPA among others. There were also recommendations on anti-Dalit, anti-Adivasi and anti-women discrimination and violence.

How it works in the UPR is that the reviewed country has the option to accept recommendations, which means that it is obliged to implement them and show results; or to challenge the recommendations; or to only note them. The more serious concerns regarding civil and politically rights, were only noted by India, and therefore even the possibility of implementation of the recommendations was not there.

Regarding the expert bodies, I will take an example of the ICCPR. Treaty bodies are required to monitor implementation of conventions by individual countries through periodic reviews that they conduct, but also to raise concerns etc. The last review of India happened in November 2024, and took place after a gap of 27 years. This is because countries are supposed to put themselves forward for these reviews. Because of delays from the Indian government, this review took place after 27 long years. It raised a range of serious concerns about more recent human rights abuses and structural shortcomings and weaknesses. The review also mentioned that several concerns raised prior to the physical review remained unanswered, and that many of the recommendations from the 1997 review remained relevant. Therefore, the overall performance was poor. A mid-term report on the recommendations made in 2024 is expected in 2027, so this is a moment for civil society to engage.

The next entity of the UN is the Special Procedures, who are the UN experts which make visits to the country to meet with civil society, authorities and understand the ground situation and share their concerns, allegations and individual cases of human rights violations.

Since 2017 there has not been a single visit of UN Special Procedures allowed into the country. In Kashmir’s case, it goes back even earlier – probably 2014 or 2015. This is very serious. Despite 15 of their requests still standing, and several communications sent, very few have received responses from the government. Even these few responses said very little in terms of content, and responding to the specific allegations raised.

All of this poor engagement with UN entities which is clearly evident, is accelerated more recently but there’s also a broader historical pattern to it. When it comes to India’s ratification of major international human rights instruments, India is a party to six of the nine major international human rights instruments but has not ratified some of the critical ones like the torture convention, the convention on migrants, protection of rights of migrants, convention against enforced disappearances etc. The fact that these are not ratified means that there’s no binding legal obligation in India towards complying with these conventions.

But conventions that have been ratified such as the ICCPR, CERD and others, India has not ratified Optional Protocols of those treaties. This means that any individual complaints or inquiries in interstate communications do not apply. India’s also made several reservations and declarations, for instance regarding the ICCPR. Specifically, for the Genocide Convention, India is one of the only 13 countries to have had made a reservation prohibiting prosecution without the consent of the national government. India has also refused to be a state party to the Rome Statute, which means that it cannot be tried or be a party in the International Criminal Court.

There is a widespread poor acceptance of these norms and international obligations, and there is a shallow engagement with them. The South Asia Collective came out with a report across the region, and India was among the poorest performers in the South Asia region.

I want to conclude with a slight rewind to 2009, which was the year of the last official visit to India of the former High Commissioner for Human Rights, Nabi Pillai. I want to quote from the statement she made: “I encourage India to speak out on its own as well as in concert with others, whenever the human rights agenda that it cherishes and seeks to pursue domestically becomes of concern elsewhere.” She also urged India to continue to support freedoms and rights wherever they are at stake and particularly regarding the alarming situation in its own region such as those in Sri Lanka and Myanmar etc. That was the high standard that India was held to at the global stage and in terms of international human rights.

It is remarkable that everything that we’ve heard the panel today speak to is a negation of that high hope from India. That is our greatest failing from what we could have been as among the founding members of the UN system and specifically the UDHR which establishes the system of human and civil rights as we know it today and India’s central role in enshrining an expansive rights framework. People like Hansa Mehta, Lakshmi Menon etc. played key roles in drafting the UDHR that applied to all people everywhere unconditionally. It is that legacy that we must draw back, not just in improving our own human rights record but also leading the push globally for a just and humane world in these difficult times all around. The question really is what can we all do to change the situation from where we are to where we should be going and where we could have been.